For the past two decades a floating cosmonaut has appeared as a recurring character in the stilled dramas of Jeremy Geddes’ paintings, an isolated observer examining the urban landscapes of modern municipal bedroom communities, the iconic weightlessness of this airy astronaut emphasizing the lonely emptiness of the cityscape. For Gen-Xers, the astronaut must be a shadow vision of David Bowie‘s iconic mariner Major Tom, who was launched, lost, and left in space in the summer night of July ‘69 when flaming boosters shot his capsule into the visionary void to float alone in synthesized silence with circuits dead.

Monument, 2022, oil on board, 332/5 x 29½”

The real astronauts of the Apollo mission that landed men on the moon returned to the ground, but Major Tom didn’t. He entered the eternity of space. Now, in Geddes’ paintings he revisits the planet he left behind, a man who fell to earth to float bemused and adrift as a suspended time traveler, a visitor from the idealistic past witnessing the hard present. The utopian idealism of the 1960s has long ago vanished since his liftoff, and he drifts ghostlike over scruffy streets, windswept and weightless, a strange visitor to this alien and ordinary planet.

Gnosis, 2023, graphite on paper, 114/5 x 233/5"

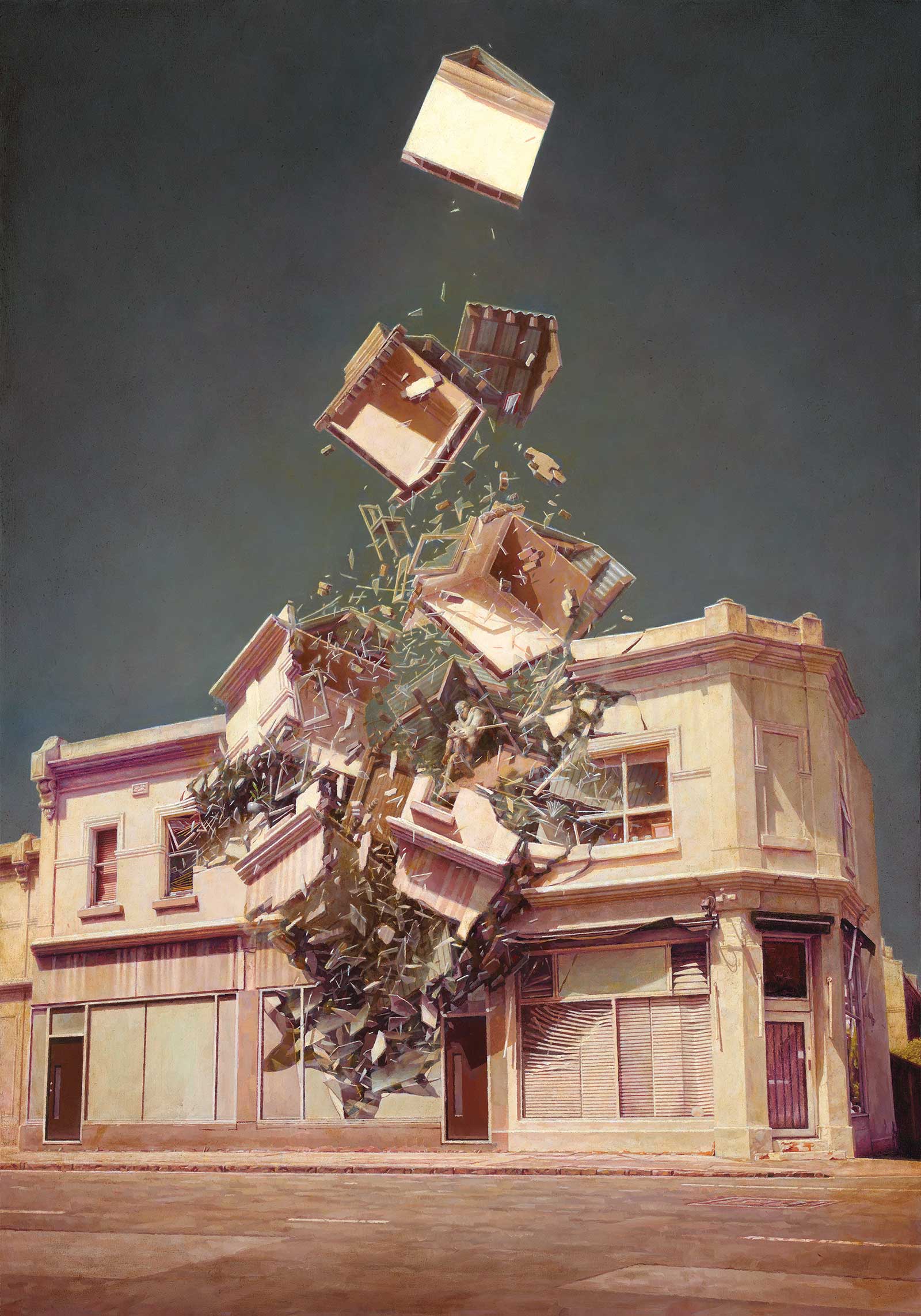

Geddes was in New York when the vicious winds of Hurricane Sandy smashed homes and pushed the ocean inland to fill the subways with seawater, and the storm surge turned streets into rivers flowing through skyscraper canyons. Walking for supplies in the calm after the storm, he was astonished to witness the damage—the face of a nearby building was peeled from its frame and thrown as rubble to the road, exposing the interiors. Once concealed and private refuges, these personal spaces were turned into an obscene scenography for an unwanted audience of strangers on the street. Armchairs and appliances, cushions and kitchens, framed and frozen by the precise cut of the stormy proscenium. The shocking but formal wreck haunted him, and surely influenced his art, as he imagined places where a strange order of missiles sliced away the walls of ordinary homes in perfect circles and rectangles.

Deluge, 2024, oil on board, 352/5 x 35"

Paradoxical damage has been inflicted. These penetrated buildings should have been smashed into chaotic and complete disorder, but only sharp sections of them have been obliterated, leaving monstrous voids in tidily framed and violent geometries of destruction. These absences mirror the plane-shaped wound in the side of the World Trade Center, an incomprehensible and arbitrary space smashed through the heart of the capitalist culture of the West by the fanatical assassins of the Jihad. They are symbols of compartmentalized and machined war, a catechism of chaos, representing the supposedly precise and digital cuts of automated drones guided by computers in the dystopian and asymmetrical violence once only imagined in hard fantasies of fighting held in hellish futures, already becoming manifest in current wars. They embody the broken apartment buildings of Ukraine, holed by anonymous rockets.

Fury 19, 2023, oil on board, 18 x 18"

The hyper-surrealism of these paintings depends upon Geddes’ extraordinarily careful technique to present the impossible as possible. He builds his paintings with the slow care and craftsmanship of a photorealist, working from models and maquettes, his scrutiny amended by imagination. Sometimes he uses computers to create mockups, or sketches, of his ideas, allowing his paint to lend the magic and mystery of mimesis to the image. This is real. This is not real. He uses the surrealist technique of juxtaposition on a grand scale, connecting unconnected objects to create cognitive dissonance. “I’m always trying to put different elements together in a way that I haven’t seen before,” Geddes says. “I remember a lecturer talking about the uncanny, the notion that you’re surrounded by objects that you know, you’re surrounded by a known world, but something about the way they are feels wrong. It’s a subtle feeling; you’re not confronted by something completely unknown; you’re confronted by objects that are not quite as they should be, and it creates this deep sense of the uncanny, and a sense of discomfort that’s hard to pinpoint. That’s always been an element I try to provoke by my choice of the different elements. It’s a bit like the uncanny valley.”

Corrosion, 2023, oil on board, 18 x 18"

In Monument, a solitary man wrapped in a fur-lined parka stares at a booster rocket irrationally lodged through the side of an apartment building, the massive machine and the structure impossibly occupying the same space, as if a malfunctioning time traveler miscalculated and dumped the misplaced ship into occupied space. Through him we are cast as witnesses to the impossible beat before a cataclysm of temporal dissonance breaks the world, mute to an awful moment held for a breath before the disrupted continuum of space and time collapses into a void of destruction. A pause, waiting for the calamity, because that moment when the rocket is held in the building is unsustainable, impossible, in poise in the second before calamity. The insanity of this second cannot hold, and loose chaos must fall upon the world to fill the insufferable vacuum: Matter must explode, the collision must complete.

Babel, oil on board, 2021, 15 x 21½"

“I love that,” Geddes says, “Timeless is the wrong word, but I love trying to make my paintings feel still…there is movement, but it also feels frozen in amber.” A city bus is vertically suspended in Gnosis, held a split second before the crash. Motionless pigeons fly above it. It is the foreboding gasp inhaled as the weird lurch and twist of an earthquake begins, the sudden hush when the birds turn silent before the bomb. Everything must change. He continues, “Paintings and still images have an interesting edge over movies or television…because you can have one frame, one image, and you never have to resolve the tension in it. I never show what happens next, so it stays in this one space. Whereas, if you had seen it in a film, you would need to see what happens next, and that may resolve it in a satisfactory way, or it might just break the spell. With a single image you have the luxury of a single point in time, when things are behaving in an odd or intriguing way, and that’s it, then you leave the rest to the viewer. It’s powerful, to set up questions that you never resolve, because I find that people bring their own meanings and resolutions to it, and those meanings are deeply personal to them…There’s a delicate balance of setting up the right questions and making sure you don’t answer them.”

Surface Tension, 2021, graphite on paper, 20½ x 20½"

This is not science fiction. Since the Apollo missions first threw intrepid astronauts outward from Earth, four generations have witnessed massive rockets launching men and women into orbit to gaze down at us from the windows of space stations circling like sparkling stars spun in a satellite net cast around the earth as we gaze at them through our screens, our heads down so we can look up. Geddes explains, “The cosmonauts, the rockets, the Apollo, these are all technology from the 1960s. They are not futuristic technologies. I’ve never painted a UFO, or a spaceship that doesn’t exist. They’re no more science fiction than if I put a 1960s fire engine into a painting. They’re old technology. They’re part of our collective consciousness, our imagistic reference—as soon as people see spacemen or cosmonauts or rockets, they think of science fiction, but in a strange way it’s not.” The space suits and thrusters that Geddes paints are antiques, nostalgic reminders of an optimistic past when apple pie and the American Dream seemed present and real, and America led the world in space exploration. The Apollo missions were the Dream in space, the mission to boldly go to the final frontier wearing the white hats of heroes, and spreading the good word of the American melting pot, promising a dream of a better future. Men walked on the moon as emblems of our good intentions.

Threshold, graphite on paper, 2024, 192/10 x 192/10"

The hovering spaceman hangs ambivalent and austere, his emotions concealed behind the deadpan mask of his helmet visor, without reaction or response to the violence he observes. But in Geddes’ new painting Deluge, floating Major Tom is melting, his suit degrading like hot wax in liquid flow and flux. A single slip of slime oozes red from the helmet seal, and the visor’s interior is gore splattered. It is a rare hint of blood and butchery from Geddes, who seldom visits the visceral, preferring the subtle tension of frozen moments of apprehension. “I’ve never really gone to fear and horror,” he says. “I certainly love painters like Beksiński, who do. He’s phenomenal [and] was one of my main inspirations, growing up. The Fury paintings are about as close as I’ve got…They’re evocative of mental states, or emotional trauma, but not physical trauma. That’s about as close as I’ve got to horror. That’s really not for me, going down that path, that’s not my aim with those paintings.” In Fury 19, a naked couple is entwined in a moment of physical desire, but the male is cleanly cut across the chest in a single slash from the super-sharp edge of a mortuary blade pressed through a bloodless body, a slice across a wax mannequin who seems to wear a second skin. An uncanny sense of deception and error creeps into the lovers’ embrace.

Signal, oil on board, 2024, 193/5 x 393/10"

There is distilled isolation in Corrosion, where a hiding man hangs from a walkway railing, desperate and alone, shrinking from the horror and terror of this alienating time. But there is hope. In Geddes’ new drawing Surface Tension, the astronaut is suspended at the open top of an unnaturally tidy vertical slot smashed through an apartment building. He floats in the open gesture of the crucified and ascendant Christ, arms wide akimbo to embrace the world, feet together as if nailed to the suffering cross, a figure of redemption raised to save the fated victims of asymmetrical, anonymous, arithmetic violence. Hidden in the exploding house of Babel an embracing couple are frozen in the jump and flux a moment after fragmentation, and tied together by a bond that will not be broken, for love is immune to time and terror. And in the drawing Silent Earth, where an apartment building stands penetrated by a circular abyss of annihilation, a glowing circle of light brightens the foreground. There may be frightening cracks in the world, but the spaceman, and the lovers, and the sublime circle are mystic witnesses to hope. The arms of the ascendant astronaut embrace the earth, and the orderly inevitability of violence is defeated by the fragile love that hides within, like a still, small voice in the storm. —

A Perfect Vacuum, 2011, oil on board, 20 x 35"

Jeremy Geddes: Periphery

January 11-February 1, 2025

4217 W. Jefferson Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90016

(310) 558-3375, www.thinkspaceprojects.com

Powered by Froala Editor